We awoke on day 3 to slightly cloudy skies and a bit of a chill in the air. You could see that the sun was desperate to break through the cloud in a few places, so ever-hopeful we packed the towels and headed off towards the famous Albanian Riviera.

The Riviera is a steep, coastal part of south-west Albania and it lies on the eastern part of the Ionian Sea. It encompasses Sarane, Himara, Dhermi, Qeparo, Piqeras, and Lukove. With the Ceraunian Mountains separating the coast from the land, it is a beautifully dramatic part of the country that offers stunning views of the sea and Greek islands, from perilously dizzying heights. The road that cuts along the side of the mountain range offers a plethora of wonderful things to see and do along the way- beaches, bays, canyons, coves, rivers, olive and lemon groves, traditional villages, ancient castles, monasteries, churches, and more- you need several days to explore this expanse.

There are several fascinating things about this area- asides from the incredible natural beauty that is in such a contrast with the beauty found just down the road in Ksamil and Sarande. The first is that many of the towns in the Himara area (Dhermi, Pilur Kudhes, Qeparo, Ilias, Palase, Vuno) are populated by a predominantly Greek community that speaks first Greek, Albanian second.

The history of the area and how it ended up in this particular situation is as long and confusing as it is bloody. In antiquity, the area was inhabited by the Greek Chaonian tribe which were one of the three Greek-speaking tribes of Epirus. The town of Himare is believed to have been founded as Chimaira by the Chaonians before passing into the hands of the Romans, and then the Byzantine Empire after the fall of Rome. Like many other areas of the country, it was then regularly set upon by various invaders such as Goths, Avars Slavs, Bulgars, Saracens, and Normans. Then in 1342, it fell under the rule of the Serbian Empire, before being subjected to almost continuous attempts at invasion from the Ottoman Empire. In the end, the Ottoman forces were made to strike a deal with the Himariotes which included the right to local self-government, the right to bear arms, exemption from taxes, and the right to their own flat This was not enough to subdue the Himariotes and the conflicts continued well into the 18th Century.

Then in 1797, Ali Pasha the Muslim Albanian ruler of the Ottoman Pashalik of Yanina raided the town of Himare because they had supported his enemy, the Souliotes. More than 6000 civilians were murdered. Two years later, Ali tried to create good relations with them after declaring their enclave a part of his semi-independent state and by financing churches and public services. His rule over Himare lasted 20 years but came to an abrupt and violent end when he was beheaded by Ottoman agents, and his head was transported to Istanbul to present to the Sultan, preserved in a dish of honey.

Then, during the Greek War of Independence, the Crimean War, and The First Balkan War, the Himariotes fought for their independence and their right to be a Greek community. In 2018, there are still ethnic tensions in the area and in October 2017, 3000 Albanian police officers arrived in Himara to oversee the demolition of property belonging to members of the Greek minority. Athens responded with a stark warning that such moves could jeopardise the ascension of Albania to the EU.

This stretch of coastline was also visited by my uncle, Edward Lear who painted and wrote about the area in 1848, and it was also visited by Lord Byron several years later, who visited as a guest of Ali Pasha.

Retracing Lear’s steps, we set off into the mountains. The road was narrow and snake-like and turned this way and that, and even back on itself as it negotiated the steep slopes of the ‘Thunder Mountains’. They most certainly lived up to their name, because as we climbed, we ascended into the thick cloud that reverberated with the guttural growl of thunderstorms. Mist obscured the road in parts, and the sides of the road had collapsed in places as we edged our way past flocks of sheep, goats, and the occasional lone cow. Here, the signs are in Greek as well as Albanian, and many of the sleepy villages look untouched and empty. Whilst the piercing red of poppies, and the soft pastels of roadside roses are still prevalent here, the landscape is much more arid and barren than the areas around Ksamil. It is still breathtakingly beautiful- with the mountains shrouded in clouds to our right and the bright turquoise of the ocean and the silhouettes of distant Greek islands on the left.

We pass through Shen Vasil, Lukove, Borsh, and various other unnamed towns- empty hotels and guest houses, bright coloured houses, and olive groves accompany us on our way. We spot many people by the side of the road, selling honey, fruit, and olives by the kilo. We ascend and descend through bottomless valleys, and reappear on top of a mountain with miles of white sand stretching out before us. We stopped for a coffee in a nameless village, and shared the time with two Norweigan bikers, riding up the coast on a rather fancy-looking BMW motorbike.

Deciding that the weather wasn’t really good enough for lying on a white, sandy beach (it kept switching from sunny and glorious, to rainy and grey), we kept on driving until we reached Porto Palermo.

A small bay, just a few kilometres south of Himare, this location was rated by the Huffington Post as the number 1 Undiscovered European Destination in 2014. It consists of a small restaurant, a manmade jetty, a church, some abandoned buildings, a castle, and a delightful little bay complete with deckchairs.

We refreshed at the restaurant overlooking the bay, and the decided to go check out the castle. This part of the coast is rich with history and as well as being home to Ali Pasha, this bay was also a Soviet Submarine base, a prison, and a military zone. For many years, no cilivians were allowed to access the area and it remained sealed off until the fall of the regime.

Today, communist-era buildings still stand with faded proclamations of propaganda emblazoned on their walls, empty buildings and a well sit in ruins, but the surrounding beach area with the mountains rising up behind it are tranquil and serene. Rumour has it that there is a tunnel running from the castle to the beach that was used by Ali Pasha to escape the Ottoman agents that turned on him towards the end of his life.

This church was built by Ali Pasha in the 19th Century. At the age of 65 he fell in love with a dancer in his harem. A young Greek-Orthodox woman, it was said to be love at first sight. They married, and Ali, a Muslim built his love this church so she could practice her religion near their abode.

We walked up towards the castle, negotiating the rocky road and the prickly silver-green and lilac thistles, we came across fig and pomegranate trees, sadly not bearing fruit at this time. As we approached the entrance to the castle, a friendly, blue-eyed Albanian guide relieved us of 200 Lek and gave us the history of the castle in a mixture of Albanian, Italian, and English.

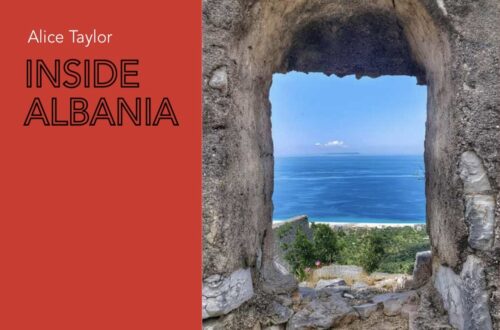

The castle is believed to date from the 15th or 16th Century, although the area has been mentioned in writings by both Strabo and Ptolemy so it is likely that it has been there in some form, since antiquity. It is unusual in its design- triangular in shape and with no courtyard, it does not even have provisions for housing horses- something that would have been required at the time. For around 8 years, it was home to Ali Pasha and his wife Vasiliki and it is believed it was not used much for military purposes as it had only 3 or 4 cannons and was strategically vulnerable from the hilltops above.

The castle itself is remarkably well-preserved and stepping inside its thick stone walls, the air is both cold and hot at the same time. As we explored its 12 rooms (including the harem, Ali Pasha’s room, and the meeting area) by phone torchlight, I wondered who had been there before us and what the walls would say if they could talk.

After exploring the murky bowels of the kalaja, we climbed up to the roof. This offered incredible views of the mountains, coast, and ocean beyond with the islands of Erikousa and Ethoni. As the storm clouds descended from the mountains and started to threaten us with droplets of cold water, we decided it was time to head back to Sarande.

The castle of Porto Palermo is fascinating and the history of the area could take up many days of reading. If you have a chance to pass through this wonderful and wild part of the world, be sure to stop to soak up some of the atmosphere at this historic location. Sit and look at your surroundings and think of all the people that have passed through there- Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Slavs, Serbs, Goths, Ottoman rulers, artists, aristocracy, communist prisoners, Soviet soldiers, and curious English girls, retracing the footsteps of her ancestor.

Follow The Balkanista!