The weather decided to be kind to us as we set off from Tirana. The sun was shining, the barometer showed 26 degrees, and I was full of excitement as we left the smoggy air of the city behind.

Taking the highway out towards Durres and driving through the flat plains of the area, I expressed a desire for byrek. Taking a turn, we drove into Lushnje with the promise of some of the best byrek that Albania has to offer. Lushnje is a quiet mid-sized city located just west of the centre of the country. in 1920 it was the provisional capital of Albania before Chieftains of Albania declared Tirana as the definitive capital city. 3km outside of the centre of Lushnje is the Savra Field which is where the first battle between the Principality of Zeta and the Ottoman Empire occurred in 1385 where Balsha II was killed. In more recent history, Lushnje, along with Fier, Saver, Gradishte, Bedat, Rrapez, and Plug was home to many concentration camps of the brutal communist regime.

The city itself is comprised of large tree-lined boulevards. Wide and expansive, they are edged with brightly coloured buildings- more so than in any other city I have seen. Bright coral complexes, pastel green and blue apartment blocks, and Mondrian-esque paint jobs draw the eye and inject some life into what may otherwise be a sleepy backstreet.

We stopped at a cheerful cafe that served us byrek with spinach and byrek with meat, washed down with dhalle. I know this yoghurt and water drink by other names; aryan or laban and it is a drink that is extremely popular in Turkey and other Arab countries. It went perfectly with the warm, flaky pastry, and the deliciously seasoned fillings. Feeling refreshed and newly caffeinated, we hopped back in the car and carried on our way.

One thing I note with pleasure about the Albanian countryside is the prevalence of roses (and other flowers) by the sides of the road. From well-tended bushes in fancy gardens to blooms that have just sprouted aside the tarmac, they come in the most vibrant magenta, orange, yellow, and peach, and sometimes where there are many in one place, you can pick up their scent wafting through the summer air. These flowers can be found in the most unlikely places, infiltrating the derelict, long-forgotten, shells of communist industry that blight the landscape, bringing light and beauty to the decrepit concrete and rust structures that scar the green and fertile countryside.

Now, this is an area for farming- field upon field of luleshtrydhe stretch for miles, olive trees and vineyards flank either side of the highway and makeshift stalls sell qeshi (cherries) by the kilo. We stop to get some from a cordial gentleman and I note their heady scent and deliciously sweet and rich flavour as I bite into the soft flesh. We continue, spitting cherry pips as we go and heading towards the mountains.

Many of the houses here perch on stilts, brightly coloured with orange terracotta roofs, they sit precariously rising above the land around them. The colour of the earth is starting to change. What was once a verdant patchwork stretching as far as the eye could see, is now feeling the effects of the start of the scorchingly hot Mediterranean summer. Patches or ochre and dusty brown earth are beginning to permeate the once velvety plains and within a few months, these lands will be parched and arid. Whilst roses still crop up from time to time, they have been replaced by the brilliant vermillion hues of the lulekuqe (poppies)- the national flower of Albania. These beautiful flowers are splashed across the landscape like drops of paint in a Jackson Pollock painting. Expressing my love for the delicate flowers with their tissue-paper-like petals, my other half stops the car and picks me a small bunch although they sadly wilt before we reach our destination.

We pass cows, sheep, and horses that graze at the side of the road, some even venture onto the asphalt and seem unphased as we zoom past. The mountains we need to climb to reach our next destination loom up ahead, layered in purples and greys against the horizon. We are in Fier County now and as the once flat earth begins to rise up around us we stop at a small roadside shop for a drink. On discovering I was not from Albania (not sure what gave it away) the owner proudly presented me with a freshly burned CD of Albanian singers, including, he assured me, Dua Lipa and Rita Ora. Here, the river wound its way down from the mountains and out towards the plain- the sky beyond was moody and punctuated with dramatic clouds- in terms of the weather, I feared the worst.

As we cross into Tepelena, the weather takes a turn and the Kelcyre Gorge mountains that tower above us are lit up with spectacular flashes of lightning and rumbles of thunder that you can feel in your bones. The hills of Tepelena are totally impenetrable- steep and unforgiving they offer little sanctuary, and small villages cling to the slopes like barnacles on a hull. The Drino river cuts its way through the valley with broad silty shores as we make our way to the birthplace of Ali Pasha. My uncle also visited this place, albeit 151 years ago, and he drew many of the vistas that we passed through, which in my opinion remain largely unchanged from his days and the paintings the made.

We continued on our way, leaving the black rumbling skies of the storm behind us and making our way to Gjirokaster. The “new town” sits at the bottom of the valley with its orange and green hotels and 70s-style tower blocks, it is nothing special and I felt a little disappointed. But as the road continued on, I saw the old part of Gjirokaster rise up before us. The fortress sits at the top, surveying the city below and rows of tiered stone houses reach up the side of the mountain.

Continuing our ascent, the tarmac changes into cobbles and we find the car struggling to grip and climb at the same time. The houses of the old quarter are some of the most beautiful I have seen and they remind me in places of mountainous parts of Spain such as Casares or parts of North Cyprus, with their narrow streets and precariously perched properties.

These buildings, adorned with small balconies and climbing roses, are just breathtaking and when we get out of the car and start walking around, I feel like I am on the set of a movie. We visit the house of Ismail Kadare, meet a few less than friendly cats, and marvel at the beautiful surroundings. I could live here I think to myself.

Walking down one of the main streets, we are confronted with the usual souvenirs- geometric woven rugs, wooden carvings, and hats and shoes made from stiff wool. But there is one shop that stands out- outside a small bronzed and wizened man sits chiselling away at slate, engraving intricate designs onto the stone. We step into his shop and it is like a cavern with stone tablets on every surface. Peacocks, donkeys, vistas of Gjirokaster and the surrounding areas seem to be the most popular subjects of choice, but then I notice something else. On one shelf is a varied selection of stone-carved hands, each with the fingers clenched into a fist, except for the middle one that extends proudly and defiantly into the air. I laugh and asked if there was much demand for stone swearing fists, and my boyfriend translated and started a heated conversation in Albanian. It turns out that this man was once a communist and he says that since the change to democracy, absolutely nothing has changed. He believes there is no difference between the two and having worked for 35 years in this job, this shop is all he has. He has nothing else and for this reason, he carves these one-fingered salutes as a message to the powers that be. I purchase a couple of tiles and we say our goodbyes.

As we progress towards Sarande, the scenery changes drastically. We climb up and up the side of one mountain, following a perilously winding road as it cuts through the layers of sedimented rock that make up the slopes. As we reach the summit and begin our decline, it is like entering a different world. The slate and granite coloured layers of rock subside and are instead replaced with rolling hills of womanly curves that are velvet to the eye and rise, fall, and ripple like rolls of soft green flesh. It is leafier hereand we stop to take a photograph at a rocky outcrop and my breath is taken away by the stunning view before me. The trees are taller and thicker here and the greens are a much deeper hue. We descend into the valley below and take a turn off to the Blue Eye. A winding terracotta path takes us right into the heart of the valley and after about 10 minutes, we are at our destination.

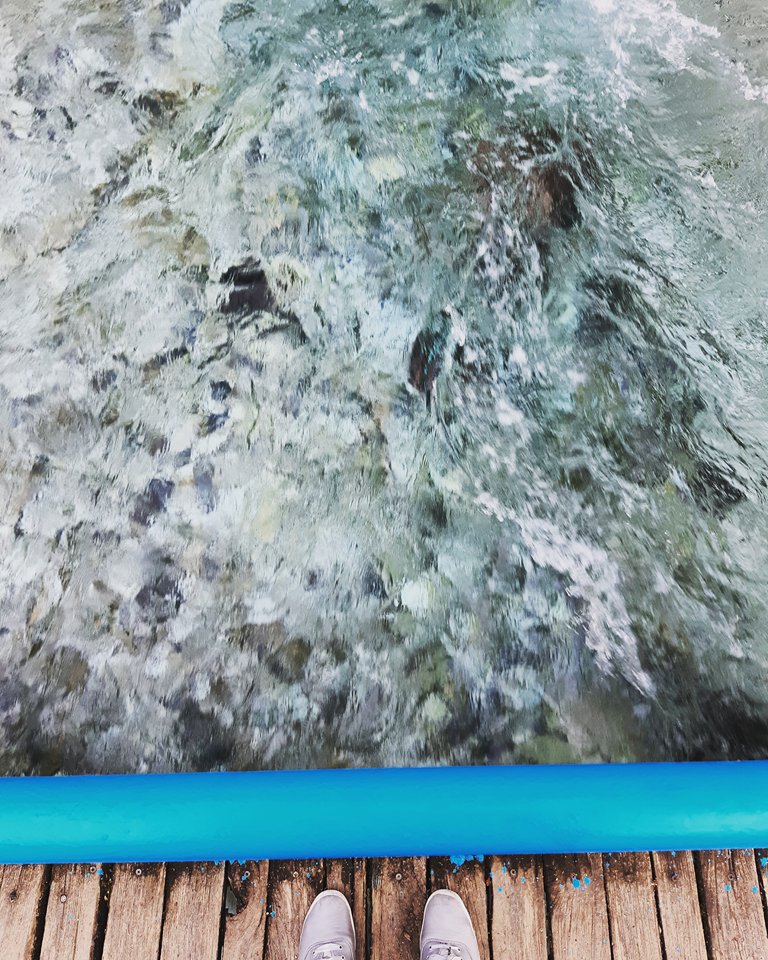

The Blue Eye is a natural phenomenon- a hole in the centre of the earth that releases bubbling, bright turquoise blue water to the surface. No one knows how far down this hole goes, and no one knows what secrets it hides, but the incredible colour of the water that springs forth, draws thousands of visitors every year. We push our way through the overgrown foliage, cross a less than secure looking bridge, and there before us is the startling blue water of the lagoon.

Fine wisps of mist lick the edges of the shore, and the bubbling of the frothy water makes me feel a little on edge. Whilst this is a truly beautiful place, there is something disconcerting about the atmosphere. I feel uneasy and on edge but for what reason, I don’t know. As we head back towards the main road, I feel relieved and less anxious. We stop at a small house perched on the far side of the lagoon and are greeted by a friendly dog and row upon row of brightly coloured beehives. I edge as close as I dare, stopping when the low drone of the buzzing bees advises me that I probably shouldn’t go much further. As we continue towards Sarande, the air smells damp and earthy and I can hear frogs chirping as I take in the air with the car window down.

It takes us 30 minutes to reach Sarande and the journey involved a heard of goats, being chased by a stray dog, and having to interrupt several cows as they strolled gormlessly down the middle of the road. The signs here are in Greek and Albanian and the countryside begins to remind me a little of Cyprus. We follow a man-made river towards the shore, and I realise it is feeding water from the Blue Eye lagoon, to the city of Sarande. I know this because the water has the same iridescent hue as the mysterious depths I saw before.

Sarande is a town built for tourists- large apartment blocks, imposing hotels, and shops selling clothes and souvenirs seem to make up the majority of the city. We arrive at our hotel just as the sun begins to set and our balcony offers an unspoilt view of the bay and Corfu in the distance. I sit staring over to the twinkling lights of Kassiopi, with the last tendrils of sunlight permeating the purples and oranges of the evening sky, and I think that my mother sat directly opposite me over 40 years ago. As she once sat in Corfu gazing at the lights of Sarande and wondering what it was like, I now sit gazing at Corfu from Sarande, thinking how beautiful it looks.

Follow The Balkanista!